Hacking together a prototype homepage in less than an hour

Some Backstory

In early 2018, my team at Arazoo were working on an interesting experimental product: a search engine specifically for lighting products.

This was the outcropping of a ton of customer development work we were doing at the time, trying to hone in on why there were problems in our customer acquisition, onboarding, and retention pipeline.

I’ll write about our customer development journey elsewhere, but to sum it up here: we found that product discovery was a huge pain in the butt for architects and interior designers. They had a notion in their head of what they wanted, but the tools available to bridge the gap between their ideal and a real-world product were limited.

The tools broke down into roughly two buckets: search and curation.

On the search side, they needed to know exactly what keywords to use in generic search engines to narrow down to the type stuff they wanted; but even if they’re precise, those generic search engines (like, say, Google) also return a whole lot of results that aren’t applicable for a design professional (for example, consumer-grade products from big box stores and chain home renovation depots). Searching was largely a problem of too much noise and not enough signal.

On the curation side, they had to work assiduously to curate their list of curated lists. Most designers do most of these things (many do all of them): subscribe to industry magazines; maintain relationships with reps from suppliers and manufacturers who match their style; follow influencers on Instagram; browse Pinterest; browse Houzz; ask around to friends and colleagues; and pilfer from past projects. An interior designer’s curated stream of inspiration and product opportunities is only as good as the attention and care they devote to curating their sources (and relationships). This works out great if you’re at the top, but it’s a big pain in the butt if you’re a little guy, or a junior designer.

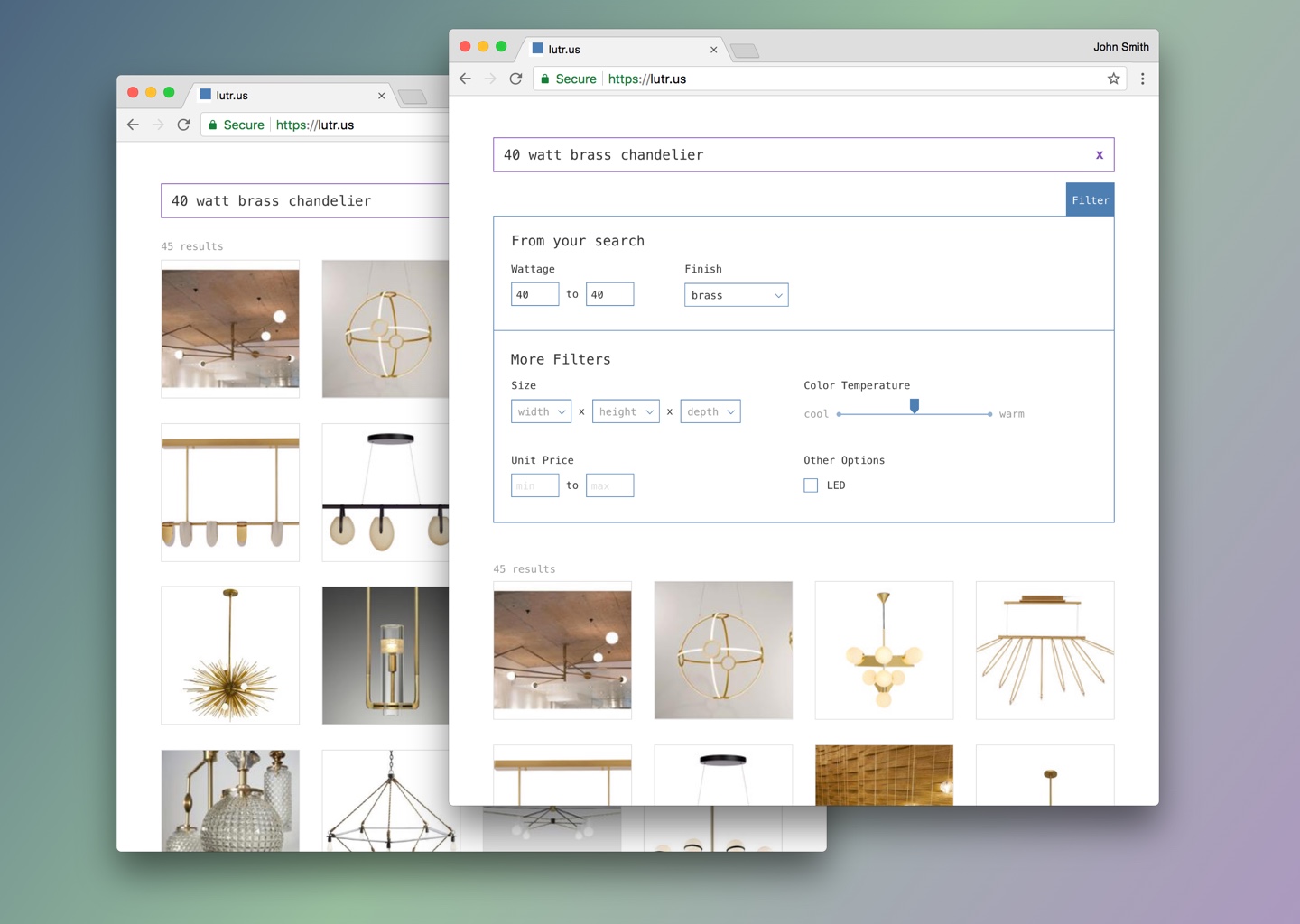

So we saw that we could basically combine some of the best of both to make a more empowering product discovery engine. We started from search, but wanted to address some of the biggest problems with search: namely, the ineffable “that”ness of the designer’s mental ideal, and the loads of irrelevant results they got from generic search engines. We would address this by giving deeper filtering criteria than a generic search engine might give, and by bringing in some of our own curation in the form of deep categorization. The thought here was basically to give designers explicit and precise control over filtering the content they see in search results, but also to do our own initial passes at preventing bad results from getting in at all and categorizing everything by styles and price ranges as they were indexed. This would allow a designer to, for example, search for “midcentury modern wooden coffee tables between $1500 and $2000, available in the New York City area” and get some cromulent results. I’m simplifying and skipping over a lot of the technical details here, but that’s the gist.

This, of course, is a huge undertaking. So to cut down scope for our MVP, we decided to focus on one vertical: lighting.

Architectural and decorative lighting is, if you didn’t know, an opaque and byzantine industry. Lights are so highly configurable that the manufacturers usually produce interchangeable/customizable parts, rather than whole fixtures, and lighting distributors are the ones who warehouse those parts, configure them, and sell completed fixtures to retailers, resellers, or direct to consumers.

This makes for a pretty complex setup for designers (some of whom are resellers) looking to get accurate lead times and prices; as opposed to verticals with fixed product offerings, the designer is at least two steps away from the people designing the product. The only source for information is the distributor, but lighting distributors are a middle man who have their own lead times and profit margins to consider, so the lead times and prices delivered to designers have some padding in them. Basically, it’s a big game of telephone, but instead of garbling a common phrase, it has the effect of making that ceiling-mounted light fixture you want for your hallway $2500 when its components cost about $250 to produce.

Transparent price information was one opportunity we saw to make a big difference here, but before that, there was just the basics of discovering existing available products that match a look, budget and location.

Making The Homepage

We had a hypothesis; we quickly started working on an actual app that could demonstrate this experience. But we also wanted to see how big our addressable market was for this. Enter a teaser landing page.

Our developers were busy working on our prototype to test out with early users we met in person, so I took the shortest route I could to getting a landing page put up.

Branding: Just Make It Consistent

We had no formal plans for the branding, name, or feel of the product. Which wasn’t really a big deal anyway; we just needed something coherent enough to serve as a test, and we could throw all of it out later. I the brand it needed to be something that felt easy, stylish, friendly and simple; these are stylish people who are seeking relief from an annoying, expansive process of digging through endless piles for occasional gems.

I started out by shopping for a domain name. I wanted to try to find something that suggested light, but wasn’t a common word (expensive; likely already taken). After some searching on namecheap, I found lutr.us. “Lutrus” sounds vaguely related to light. It’s not a real word, and no one’s competing for it. The domain cost $0.88 a year. I bought it.

So now I had a name to use for the product. I next made a few arbitrary visual decisions. I picked some base colors to use: white, charcoal, serge blue, muted lilac, and forest green. I decided to push a simple+technological feel by using a monospace font, Menlo. I wanted you to feel like you were talking right to the computer, an open, honest, simple dialogue with a powerful engine.

I made a single-page homepage with a few hero sections for the big features; the top is a CTA to sign up for early access (i.e., join our mailing list), then a section about search, then a section about filtering, then another CTA to sign up. I added some highly speculative mockups to the feature sections.

I put all this in a git repository.

LAMP but without the AM (and a different P)

To host it, I spun up a vanilla Ubuntu 16 vm on DigitalOcean and cloned my git repo onto it. Even though it was static content, I went with a vm instead of hosting the files from S3 for a couple reasons. First, S3 (and, really, AWS in general) is a terrible user experience! I didn’t want to have to do this via uploading (and reuploading) files in a web interface. Second, it was a lot easier and cleaner to spin up a new vm in DO than it would be to go ask my programmers for permission to make a new bucket etc etc in S3. Third, I wanted to be able to actually host the experimental prototype there in the future.

So I had my code on the vm, and I had my domain name. DO made it really easy to to the ns routing to point my cheap domain at the virtual machine. All I had to do was actually serve the page.

I was starting to get it set up with Apache, when I got pulled into a meeting. This was at about 4pm; we had planned to get this site up and running before 5pm. Uh-oh.

Fast forward 45 minutes, and I ducked out of the meeting to address this. I still hadn’t settled on the final graphics or copy for the first run of the page, though that didn’t really matter; I just needed to get some live version up so that I could set up a Google AdWords campaign (it’s poor hygiene, and also something Google dings you for, to point an AdWords campaign at a page that isn’t live yet). Short on time, I pulled out one of the most fun tricks I knew: python -m http.server.

Yes, that’s right, I served a static page from a temporary python server in production!

Well, almost. It’s not that bad. I used certbot to get an ssl cert then did it over https. You can see the setup for what I did in the repo.

Measuring It

I also added FullStory and Google Tag Manager to the homepage, so we could watch sessions and measure stuff. We ended up getting a pretty positive response, and recruited a few dozen people who were willing to talk to us and do user testing sessions on the prototype.